Update on surveys

The survey process is slow. I am sure many of you, sitting in your offices in the United States, are remembering some marketing survey that a handful of your colleagues conducted in a number of hours or days, and are wondering how in the world is it possible to take this long conducting a survey? Well, first let me remind you that there are different worlds. The "first world", "second world", and third world. I belong to the second at present. And the motivations behind the survey are many, the process being, in this instance, as important as the results. In addition, technological, cultural, and financial obstacles have each had their spotlight and at present refuse to be thrown from the stage.

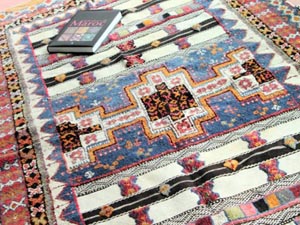

The survey process is slow. I am sure many of you, sitting in your offices in the United States, are remembering some marketing survey that a handful of your colleagues conducted in a number of hours or days, and are wondering how in the world is it possible to take this long conducting a survey? Well, first let me remind you that there are different worlds. The "first world", "second world", and third world. I belong to the second at present. And the motivations behind the survey are many, the process being, in this instance, as important as the results. In addition, technological, cultural, and financial obstacles have each had their spotlight and at present refuse to be thrown from the stage.Progress: I have had interviews with Bazaars (essentially tourist shops and carpet stores) from Zagora to Ouarzazate to Taznuckt. Spent a whole day (or two if you count the obligatory overnight in Ouarzazate) traveling to, surveying in and returning from Taznuckt. I completed four surveys and considered the trip a success. Why? Consider this: interview number one: an artisan carpet cooperative. The guys running the shop showed me hundreds of gorgeous carpets from around the region, and explained how the great variety of motifs had meaning or the style a particular purpose: some carpets had little ropes woven into them that hung off each side.

These were intended as travel carpets: lighter weight easy for travel, large to create an instant floor of a tent or tea area in the desert, ties on the edge so that the carpet and all of its contents could easily be gathered into a bundle and carried or tossed over a donkey. They showed me books developed by French or Germans detailing the history and precise village in Morocco where each originated. I learned a great deal; moreover my appreciation of the wealth of history, information and culture enveloped in these creations has grown tremendously.

These were intended as travel carpets: lighter weight easy for travel, large to create an instant floor of a tent or tea area in the desert, ties on the edge so that the carpet and all of its contents could easily be gathered into a bundle and carried or tossed over a donkey. They showed me books developed by French or Germans detailing the history and precise village in Morocco where each originated. I learned a great deal; moreover my appreciation of the wealth of history, information and culture enveloped in these creations has grown tremendously.I asked them about current problems and practices in selling and shipping their rugs. There is little traffic through Taznuckt as it is a bit out of the way... so most of their sales come from getting as much product they can to centers of tourist commerce, such as Marakesh, Fes and Agadir. These gentleman had begun using email to correspond with French and American contacts, selling piecemeal items via such communications - emailing photos of particular carpets, giving dimensions and guesstimates of shipping costs.

I quiered them about shipping the carpets when required. They attempt the Post Office sometimes, but often the service is too slow for their requirements or the weight over 32 kilos, the PO limit. They usually end up driving the carpets to Marakesh and charge the customer nothing for their travel time. Never even considered it. As they are already accustomed to taking photos of their work, recording dimensions, have every one of the hundreds of carpets catalogued, and are familiar with email and the internet, I asked if they were interested in learning how to upload their carpets to a website, such as Ebay and selling online. They were very eager, and begged me to return to assist them. A new potential project born. And another need to develop a workable, dependable, and affordable shipping system for the region.

The second Bazaar turned out to be an association. At first he didn't seem very interested in my project and rushed (a relative term) through the survey. Then, he asked me if I had time, pulled his chair close to me and recounted the history of the association. He and his family are heavily involved (the sales end) in the womens' association in the village 2 km from Taznukht. All these women are constantly hand-weaving carpets on looms in their little adobe homes. He returned to Taznuckt to sell the carpets for them, the difference being that a Bazaar connected to the assocation would return all or most of the profits to each individual woman responsible for making it (in theory). He said that they have done well. Last year he visited an international craft fair in New York. This year he plans to exhibit at one in Paris. He said they sell well at the fairs, and the networking opportunities are even more helpful. He would like to be on the road more, traveling to a good number of fairs. However, he is the only young, educated individual in the entire association, and if his time is spent on the road, there is no one to handle the sales at the Bazaars. I asked if there was no one else in town to whom he could turn over these responsibilities. He said that the largest issue was trust. There was no one he could trust. He "kidnapped" me and drove me out to the village, introduced me to adorable little old women weaving on looms, chattering away to me in Shilha (Berber) and me responding in Arabic while they shook their heads, not understanding a word. The young man begged me to come back and help them with websites, or other business development options. (And proceeded to question me as to a relationship, and called dozens of times in the space of an evening the following week to profess his love, as often happens with young men here...there is a reason you often have to act like a snob when traveling solo here.)

The second Bazaar turned out to be an association. At first he didn't seem very interested in my project and rushed (a relative term) through the survey. Then, he asked me if I had time, pulled his chair close to me and recounted the history of the association. He and his family are heavily involved (the sales end) in the womens' association in the village 2 km from Taznukht. All these women are constantly hand-weaving carpets on looms in their little adobe homes. He returned to Taznuckt to sell the carpets for them, the difference being that a Bazaar connected to the assocation would return all or most of the profits to each individual woman responsible for making it (in theory). He said that they have done well. Last year he visited an international craft fair in New York. This year he plans to exhibit at one in Paris. He said they sell well at the fairs, and the networking opportunities are even more helpful. He would like to be on the road more, traveling to a good number of fairs. However, he is the only young, educated individual in the entire association, and if his time is spent on the road, there is no one to handle the sales at the Bazaars. I asked if there was no one else in town to whom he could turn over these responsibilities. He said that the largest issue was trust. There was no one he could trust. He "kidnapped" me and drove me out to the village, introduced me to adorable little old women weaving on looms, chattering away to me in Shilha (Berber) and me responding in Arabic while they shook their heads, not understanding a word. The young man begged me to come back and help them with websites, or other business development options. (And proceeded to question me as to a relationship, and called dozens of times in the space of an evening the following week to profess his love, as often happens with young men here...there is a reason you often have to act like a snob when traveling solo here.)The third Bazaar was much more business-like, and appeared had less time for me, but did explain their attempts at shipping carpets abroad, customers refusing shipments once it finally arrived, driving loads to Tafroute, Agadir or Marakesh (seven hours away) to sell or ship, and not charging or marking up product for the additional traveling expense. There was no trustworthy, cheap, or feasible shipping option in the region.

And on and on it went. Each bazaar survey takes an average of an hour: first to explain to them it's purpose, then to discuss whether it would be useful in their minds to fill it out for me, then to gather around on stools with fellow sales clerks to read the Classical Arabic (they speak Dirijia, a simplified version of classical, as do all Moroccans and all Arabic cultures, but the only written language is Classical, therefore sadly tedious and often misunderstood) outloud to each other. Often they would stop and ask me to interpret the Classical Arabic for them into Dirija. I read a few words of Classical, and went over good portions of the survey with a tutor to make sure the translation successfully communicated what the original intended in English. I find it ironic that they are asking me to explain their written language to them in their native tongue, when it is I that am a non-native speaker/reader. (I did find out last week, from a friend who went over the translations with his very helpful tutor, that the Arabic was distinctly a translation, and did not flow well as written. He is working with his very helpful tutor to retranslate, as my work was done in the summer months when all the teachers make a mass exodus to the cities for their summer vacations. After reading the entire survey of 25 questions aloud, the clerk will slowly procede to fill it out, maybe starting with number one, jumping to question 5, and down to 11 before returning to 2 at my reminder. There is a box for yes (nam) and a box for no (la). Sometimes they start by putting an "x" through la to indicate "yes" (crossing off the option they do not mean), but then will reach a question where they want to answer "no" and then ask me which box they should fill. These surveys provide a multitude of insights into the difficulties of having different written and spoken languages, of the new concept of a written survey, etc.

From these alone, I've learned a great deal about the challenges of development progress in Morocco. Consider if you grew up speaking one language (Tashelheight) with your parents and little friends. Then you went to the village nearby when you were old enough and everyone spoke a totally different language (Dirija) Your mother responded to friends in this new language, and slowly you learned this new tongue. Then she turned on the TV and you saw an entertaining show with white people in yet another strange language (French). Slowly you picked up words and whenever you walked along the street and saw a white stranger, you eagerly called to them in the words you learned: "Bonjour! Ca Va?!" ? Then you went to school, sat down and the teacher tapped on her desk, smiled and addressed you with yet more strange words. Over the next thirteen years (if you stayed in that long), you would learn to speak and write in this very complicated language (Fusha, classical Arabic). You were proud when your parents turned on Al-Jazeera news and you could understand a good portion of the latest events in the Middle East in this language your teacher spoke. After a few years, French was introduced, a few years later English added to your courses: language number five and you're only fifteen. Maybe you never had to write another word in Fusha for the next decade, and then an American comes along and asks you to read two full pages of this complicated Fusha, and then respond to the questions. It might take some time.

Cultural obstacles: during the month of October, shortly after the surveys were completed, copied and ready to be distributed, Ramadan started. All the cafes across Morocco (especially in more rural areas) were closed. Tourists (and me ;) often had to wander to little hanuts (shops) and buy crackers and tuna for lunch. Or agree to make a cafe owner make an omelette just for you, knowing he couldn't eat or drink until the sun went down, but just watching you fill your little stomach. Where is one to find tourists if not sitting in the little cafes where they can write on a survey? Patience until the month was over.

Teamwork: over the long period of time it has taken to develop and pass out surveys, I have found a partner in Abdelladim, a local guy: young, eager, motivated, and educated as a lawyer. I began to realize the treasure I had found when he called me one day and asked to meet, asked how the surveys were coming along and wanted a portion to spread among a team of young guys who would distribute them. Since then, we have met for hours on end, discussing our findings, planning our next places or discussing the slow progress of the guys he engaged in the project. Before I left for Azrou, we spent three hours a night, three nights that week vigorously recording the data (one reading answers outloud, marking them down, then inputting them into Excel spreadsheets we had created). After a time Abdim wanted to learn some of my techniques, how to input data into Excel. We discussed the best way to display the information for entry and reading results. We would take turns with the computer and quickly he caught on, and followed the process and reasoning behind each step. Once in a while a random subject would come up and we would engage in some intellectual conversation, him with patience enough to explain and write down lists of new vocab related to the subject in Arabic for me, and I, in return, sharing the English equivalents.

In Ouarzazate, as I was having a difficult time during Ramadan finding tourists (or at least ones who had the patience in the middle of their vacations to fill out the page) I left them with a friend at the front desk of a hotel. Two weeks later, I returned and he handed me a stack of thirty surveys filled out. I decided it was important to find a great variety of tourists (cheap hotels, top-of-the-line chains, fancy restaurants, cafes, carpet co-ops, etc.) and befriended hotel owners and carpet co-op salesmen, leaving a stack at three additional locations for tourists to fill out when the checked out of the hotels or paid their cafe bill. (I had breakfast at a fancy hotel, asked for just an omelette, hoping it would be cheap, for the chance of quiering a handful of leisurely tourists breakfasting before the day's outings. I made friends with the staff and approached each table with business cards and surveys in hand, was introduced by the manager, and handed out pens and surveys as they nodded in agreement or babbled away in French. I got my bill: 50 dirhams ($5). I almost fainted. Last time I would attempt that. I returned that evening just to pass out surveys, but found the dining room a mass chaos of groups chattering at every table or headed back to the massive buffet. Way to chaotic to enter. That's where the front desk came in handy.)

I'm not finished, but getting closer and much wiser for the lengthy, cross-season, region-wide attempts, team-building project it has become.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home